As a historical researcher, I have walked through many burial grounds, but few have impressed upon me the fragile nature of memory as deeply as St. Peter’s Catholic Cemetery in New Iberia, Iberia Parish. This cemetery is more than sacred ground; it is a historical landscape layered with devotion, loss, and uncertainty. Some burials here date back over two centuries. Yet for thousands of individuals believed to lie beneath its soil, the precise location of their graves has been lost to time.

The scope of the problem is staggering. Roughly 11,000 names are associated with this cemetery, but the locations of nearly 6,000 of those burials are unknown. At the same time, approximately 300 grave sites have been physically identified but lack names. This imbalance—names without places, places without names—presents a profound challenge for historians, genealogists, and families alike. Among those whose resting places are uncertain are Hildebert Theriot, his wife Louise Elmina Delahoussaye, and his parents, Hubert Theriot II and Marie Rosalie Romero. They are remembered in records and family histories, yet their exact burial places remain uncertain—a reality shared by thousands of others.

Understanding how such loss occurred requires stepping into the past. Early record-keeping at the cemetery was inconsistent, and two destructive fires eliminated many original burial registers. During periods of crisis, particularly during Yellow Fever outbreaks, burials sometimes occurred rapidly, with families informing church authorities only afterward. When documentation was made, it often relied on temporary landmarks: the name of a neighbor buried nearby, a prominent tree, a fence line long since removed. Over generations, these reference points disappeared.

Movement of remains compounded the confusion. Some burials were relocated to other cemeteries; others were brought into St. Peter’s with incomplete documentation. Headstones deteriorated under Louisiana’s humid climate, inscriptions fading into illegibility. Time, weather, and human necessity worked together to erode certainty.

Yet this is not simply a story of loss. It is also one of dedication and recovery. The cemetery’s caretaking leadership has undertaken remarkable steps to bridge the divide between names and graves. Recognizing that living memory still surfaces in quiet ways—flowers placed on otherwise unmarked sites—they initiated what they call the “Flower Project.” Cards have been placed at roughly 260 unnamed graves, inviting visitors to share knowledge. This approach treats the cemetery not only as an archive of stone and soil but as a living conversation with the community.

At the same time, a comprehensive database has been built by drawing on older spreadsheets, handwritten 3×5 index cards, and church burial books. The result is a growing digital repository of names and associated details. Each addition, however small, is a step toward restoring identity. Known graves have been indexed through Find-a-Grave, and GPS coordinates now anchor many sites to precise locations, ensuring that future generations will not face the same scale of uncertainty.

Walking the grounds, the cemetery’s layout reveals both order and the passage of time. The main entrance opens on French Street, with a smaller pedestrian gate nearby. Two principal walkways intersect—one running north–south, the other east–west—forming a simple cross pattern. Plots are designated alphabetically: A, A1, B, B1, C, D, and so on. Within each plot, burials are further described as left or right. Yet not all rows are straight, a subtle reminder that expansion and adaptation occurred over many decades. In the rear lies Section R, named for the family whose land donation made the cemetery possible. Even in its physical organization, history shows through.

For historians, unidentified and missing graves create profound challenges. Without a fixed location, we lose spatial relationships that help us understand family groupings, social networks, and community structure. A cemetery is more than a list of names; it is a map of human connection. When that map fades, so too does part of our understanding of the past.

Still, I leave St. Peter’s with cautious optimism. Each database entry, each GPS coordinate, each conversation sparked by a small card placed beside flowers represents resistance against oblivion. The work here acknowledges a hard truth: we may never recover every identity. But the effort itself honors the dead and, in doing so, restores meaning to the living.

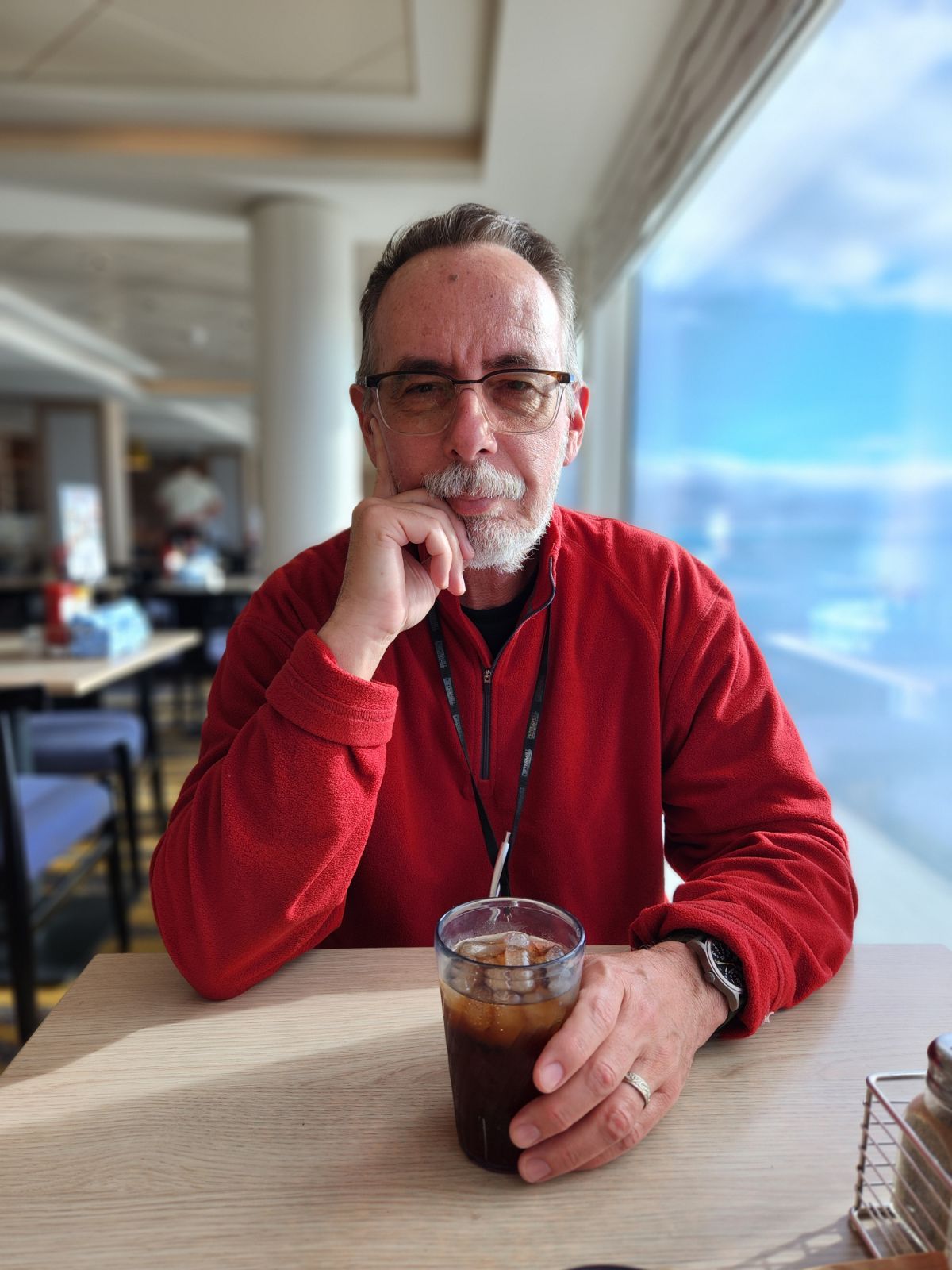

Portions of this post were produced with the assistance of LLM GPT-5 from my own detailed, reiterative prompts. The photograph of St. Peter’s Cemetery was taken by the author.