When we think of California during the Civil War era, we often picture a far-off frontier detached from the conflict that tore the nation apart. However, a closer look at the Golden State’s history reveals a complex landscape of divided loyalties and pro-Southern sentiments that have long been overlooked. This blog post explores the surprising prevalence of Confederate sympathizers in early California, challenging our understanding of the state’s role in this pivotal period of American history.

California’s Divided Population

In the years leading up to the Civil War, California experienced rapid population growth due to immigration from both free and slave states. The 1852 state census counted 223,856 non-Native American residents, growing to about 380,000 by 1860. This influx of settlers brought with them their ideals and political leanings, creating a diverse and sometimes divided populace.

Southern California, in particular, attracted many former residents of Southern states. Helen B. Walters notes, “There was reason for Southerners liking Southern California. They found life there similar to ‘home.’ Both lands possessed pastoral contentment where time weighed lightly. Whereas they left an economic system based on plantations, they found one based on ranchos. They exchanged raising cotton for raising cattle.”[1]

The Political Landscape

The 1860 presidential election highlighted California’s political divisions. Abraham Lincoln won only 10 of the state’s 44 counties, mostly in the San Francisco area. The Southern wing nominee, John Breckinridge, carried 17 counties, including Los Angeles and San Diego.[2] This electoral map foreshadowed the pro-Southern sentiments that would emerge during the Civil War.

Estimating the number of Southern sympathizers in California was challenging. General Sumner reported in the spring of 1861, “The Secession Party numbers are about 32,000 men.”[3] However, this figure likely underestimated the state’s true number of Confederate supporters.

Secessionist Strongholds

Pro-Confederate sentiment flourished in several California communities. Los Angeles attracted many Southern sympathizers, with John W. Robinson noting that emigrants from Texas and border slave states poured into Southern California in the 1850s. [4] El Monte became a hotbed of Confederate activity, serving as a training camp for recruits and overwhelmingly rejecting Lincoln in the 1860 election.[5] [6] San Bernardino saw Confederate enlistment camps organize in the surrounding hills, prompting a Unionist newspaper editor to report rampant secessionist sentiment and violence in the streets. [7] In rural Tulare County, Visalia gained a reputation as a stronghold of Confederate support, with some claiming it had the highest proportion of Confederates outside the South. [8]

The Impact on Daily Life

Pro-Confederate sentiments profoundly affected daily life in these strongholds. The education system faced disruption as many teachers, sympathetic to secession, refused loyalty oaths and fled south. [9] The legal system plunged into chaos, with courts struggling to handle cases against citizens accused of Southern loyalty. [10] Commerce suffered as residents boycotted Union shopkeepers. [11] Even religious life fractured, with ministers taking sides in their prayers and congregations openly displaying their loyalties. [12]

Influential Voices

Two prominent figures emerged as influential voices for pro-Southern sentiments in California: Henry Hamilton and Colonel Edward J. C. Kewen.

John W. Robinson, “Colonel Edward J. C. Kewen; Los Angeles’ Fire-Eating Orator of the Civil War Era,” Southern California Quarterly 61, no. 2 (Summer 1979), 165. Courtesy of Huntington Library. [Colonel Edward Kewen on the left and Henry Hamilton on the right.]

Henry Hamilton, editor of the Los Angeles Star, was particularly vocal in his support for the South. His outspoken views led to his arrest on treason charges in October 1863. He was briefly held at Drum Barracks in Wilmington before being sent to Alcatraz.[13] Despite this setback, Hamilton returned to Los Angeles and continued criticizing the government and President Lincoln.

Colonel Edward J. C. Kewen, known for his dynamic public speaking and mastery of classical rhetoric, was elected to the state assembly in 1862. His fiery speeches and pro-Southern stance soon drew the attention of federal authorities. Like Hamilton, he was charged with treason and sent to Alcatraz via Drum Barracks. After two weeks of confinement, Kewen was allowed to declare allegiance to the United States and returned home to a crowd of supporters.[14]

The Bella Union Hotel: A Secessionist Hub

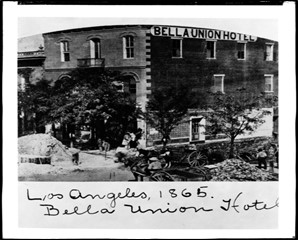

USC Libraries, “View of the Bella Union Hotel in Los Angeles, showing workers around mounded dirt and rubble,” Libraries.usc.edu, accessed March 30, 2022, https://digitallibrary.usc.edu/asset-management/2A3BF1GM9IV?FR_=1&W=1502&H=717, an image from the California Historical Society Collection, 1860-1960.

The Bella Union Hotel in Los Angeles became a focal point for pro-Southern sentiment and activity. It served as a gathering place where the area’s pro-Confederate majority could openly express their loyalty to the Southern cause. A journalist of the time vividly described the Bella Union Hotel. “The most noted Secessionist rendezvous in the whole city…I have proposed to the landlord to call it the ‘Belly Union,’ as many of the patrons get pot-gutted the moment any expression of sympathy is made for Uncle Sam. All my surroundings are ‘Dixies.’ Dogs bark it, assess and mules bray it, and bilious bipeds whistle it. The whole air is full of it.”[15] The hotel was known for its pro-Southern atmosphere, where patrons sang songs like “We’ll drive the Bloody Tyrant from our native soil” and “We’ll hang Abe Lincoln to a tree.”[16]

Confederate Monuments in California

California hosts several Confederate monuments, surprising remnants of its complex Civil War-era history. These memorials reflect the influence of the Lost Cause ideology, which sought to reframe the Confederacy’s legacy positively. The Hollywood Cemetery in Los Angeles features a six-foot granite monument erected in 1925, marking the West’s first major Confederate memorial [17]. The Jefferson Davis Memorial Highway project placed markers across the country, with San Diego receiving California’s first in 1926 [18]. Other notable sites include the Alabama Hills near Lone Pine, named after a Confederate warship [19], and the Robert E. Lee Tree in Kings Canyon National Park [20]. In contrast, California also features Union monuments like Sacramento’s Memorial Grove, which promotes reconciliation by incorporating trees from various Civil War battlefields [21].

Conclusion

California’s role in the Civil War era is often overlooked due to its geographical distance from the main theaters of conflict. However, the state experienced significant internal divisions, with entire communities siding with the South and the Confederacy.

The prevalence of pro-Southern sentiments in early California, as evidenced by secessionist strongholds, influential figures like Henry Hamilton and Edward Kewen, and the existence of Confederate monuments, challenges the common perception of California as a solidly pro-Union state during this period.

This complex history serves as a reminder that the Civil War’s impact reached far beyond the battlefields of the East, shaping political landscapes and social dynamics even in the far western reaches of the country. Understanding this often-overlooked chapter of California’s history provides valuable insights into the state’s development and the enduring legacy of the Civil War across the entire nation.

Bibliography:

[1] Walters, Helen B. “Confederates in Southern California.” The Historical Society of Southern California 35, no. 1 (March 1953): 41–54.

[2] Talbott, Laurence F. “California Secessionist Support of the Southern Confederacy: The Struggle, 1861-1865.” (Ph.D. diss., The Union Institute, 1995).

[3] Walters, Helen B. “Confederates in Southern California.”

[4] Robinson, John W. Los Angeles in Civil War Days: 1860-65. Los Angeles: Dawson’s Book Shop, 1977.

[5] Walters, Helen B. “Confederates in Southern California.”

[6] Woolsey, Ronald C. “The Politics of a Lost Cause: ‘Seceshers’ and Democrats in Southern California during the Civil War.” California History 69, no. 4 (1990): 372–83.

[7] Robinson, John W. Los Angeles in Civil War Days: 1860-65.

[8] Gilbert, Benjamin Franklin. “The Confederate Minority in California.” California Historical Society Quarterly 20, no. 2 (June 1941):154–70.

[9] Walters, Helen B. “Confederates in Southern California.”

[10] Ibid.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Woolsey, Ronald C. “The Politics of a Lost Cause: ‘Seceshers’ and Democrats in Southern California during the Civil War.”

[13] Robinson, John W. Los Angeles in Civil War Days: 1860-65.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Krythe, Maymie R. “Daily Life in Early Los Angeles: Part IV: Angelenos Took Their Politics Seriously.” The Historical Society of Southern California Quarterly 36, no. 4 (December 1954): 322–37.

[17] Waite, Kevin. “The Lost Cause Goes West: Confederate Culture and Civil War Memory in California.” California History 97, no. 1 (February 2020): 33–49.

[18] Ibid.

[19] Ibid.

[20] Ibid.

[21] Harris, Brendan A. “The People of California are Devoted to the Constitution and Union – California during the American Civil War” (master’s thesis, Southern New Hampshire University, 2020).

This blog post summarizes a much more detailed research project I completed in May of 2022: “A History of Pro-Secessionist Sentiments in California, leading up to and during the American Civil War” during my graduate studies at San Jose State University. I used the LLM Claude 3.5 Sonnet to prepare this post based on my former research, adding my final edits before publishing.

The featured image for this post was generated by the WordPress AI Assistant from the key phrase “Los Angeles in the 1860’s.”