One solid clue in identifying slave ownership among our ancestors can be found by comparing the 1860 U.S. Federal Population Schedules (Census) to the 1870 Census. Both the 1860 and 1870 Censuses asked about wealth in the form of real estate and personal estate. If we find an occasion where an ancestor, generally those from the southern states, had a marked decrease in wealth over these ten years it may indicate slave ownership before the Civil War. I have such an example in my family.

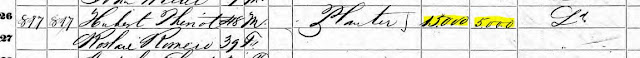

Here, we see 1860 census information for Hubert Theriot (about 1813 – 9 Mar 1881). Notice his reported real estate ownership is for $15,000. His personal estate was $5000.

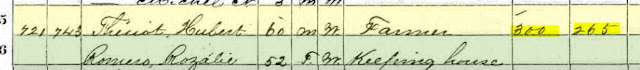

Now compare this to the same self-reporting ten years later and after the War Between The States. There was a marked reduction in capital where his real estate is $300 and his personal estate is $265.

This cannot prove slave ownership on its own. Hubert and his family lived in the deep south during the War – Iberia Parish, Louisiana – and could have lost property in other ways due to the war. We need to dig deeper. In 1870, many formerly enslaved people were still geographically close to their previous slaveholders. Enslaved people would not have appeared on the regular 1860 Census, but now, as free people, they are seen on the 1870 Census. Look up and down the page from where your ancestor appears in the 1870 Census. In Hubert Theriot’s case, the evidence is clear.

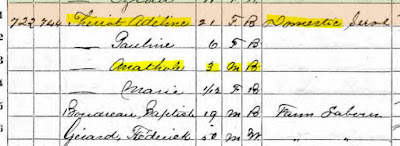

Here is the same 1870 Census page shown above. Notice just below Hubert’s family, we now find a 21-year-old black woman and three children below her. They are Adeline Theriot, 21 years old; Pauline, six; Anathole, three; and Marie, one-month-old. Wow! Amazing. My family just got bigger.

Taking the surname of your previous slaveholder happened in less than half of all instances, but it did take place. In this example, the evidence for this point is convincing. Notice also Adeline lists her occupation as “Domestic ___”. I’m betting that after her emancipation, she just stayed on with the Theriot family – now as an employee. We cannot know if Pauline, Anathole, and Marie were Adeline’s children because the 1870 Census did not ask for relationships.

From here, we can dig even deeper. In 1860, the federal government took a count of slave ownership known as the 1860 Slave Schedule. This was concurrent to the 1860 Population Schedule. Here, I found a Hubert Theriot from the same parish reporting the age and sex of enslaved people. I know this to be the same Hubert Theriot from other records. According to this document, Hubert held ten slaves – both male and female – ranging in age from 40 to one year old. Now consider this: Adeline was 21 years old in 1870. She would have been 11 years of age in 1860. And we find an 11-year-old female on the list of enslaved people held by Hubert Theriot. Circumstantial but noteworthy.

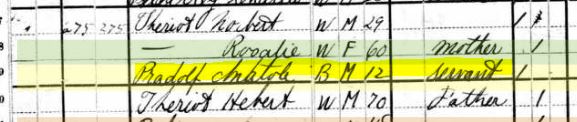

One last observation. Going forward, we find my Hubert Theriot in the 1880 Census. Hubert and his wife, Rosalie, lived with their son Norbert. Also listed is a young man named Anatole Pardolf, age 12, a male black. His role is “servant.” Remember young Anathole Theriot, age three, from the 1870 Census? The surname is different, but everything else lines up.

More investigation can be done here. Traditional African American genealogical research methods should be followed. This would start with looking for records in the Freedman Bureau and Freedman Bank collections. I’d also look for property deeds and press accounts linked to Hubert Theriot leading to 1864 (Civil War). Tracking Adeline, Pauline, and Marie (not living with Hubert in 1880) would be interesting, too. Lastly, two other persons residing with Adeline in 1870, a 19-year-old male black and a 50-year-old white Frenchman, both Farm Labor. Who are they?

All images from Ancestry.com.